| Who is it? | Inventor of Bouncing Bomb |

| Birth Day | September 26, 1887 |

| Birth Place | Ripley, British |

| Age | 132 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 30 October 1979(1979-10-30) (aged 92)\nLeatherhead, England |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| Resting place | St Lawrence's Church, Effingham, Surrey |

| Residence | Effingham, Surrey |

| Occupation | Scientist, engineer and inventor |

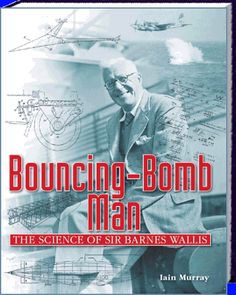

| Known for | Inventing the bouncing bomb |

| Parent(s) | Charles William George Robinson Wallis Edith Eyre Ashby |

| Awards | Albert Medal (1968) Royal Medal (1975) |

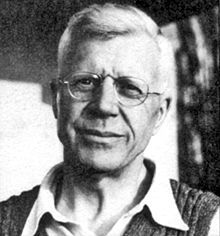

Barnes Wallis, the renowned British inventor, is hailed as the mastermind behind the creation of the Bouncing Bomb, a groundbreaking innovation that played a significant role in the success of the British Royal Air Force during World War II. As of 2025, his net worth is estimated to be an impressive $14 million, a testament to his exceptional contributions to the field of engineering and his numerous patents. With his unwavering dedication and genius, Wallis' inventions continue to impact the world, solidifying his position as one of the greatest inventors in British history.

Barnes Wallis was born in Ripley, Derbyshire to Charles william George Robinson Wallis (1859–1945) and his wife Edith Eyre Wallis née Ashby (1859–1911). He was educated at Christ's Hospital in Horsham and Haberdashers' Aske's Hatcham Boys' Grammar School in southeast London, leaving school at seventeen to start work in January 1905 at Thames Engineering Works at Blackheath, southeast London. He subsequently changed his apprenticeship to J. Samuel White's, the shipbuilders based at Cowes on the Isle of Wight. He originally trained as a marine Engineer and in 1922 he took a degree in engineering via the University of London External Programme.

Wallis appears as a fictionalized character in Stephen Baxter's The Time Ships (though its birthdate is not the same, 1883 instead of 1887, since he says he was eight when the Time Traveller first used his machine), the authorised sequel to The Time Machine. He is portrayed as a British Engineer in an alternate history, where the First World War does not end in 1918, and Wallis concentrates his energies on developing a machine for time travel. As a consequence, it is the Germans who develop the bouncing bomb.

He left J. Samuel White's in 1913 when an opportunity arose for him to work on airship design and then aircraft design. He worked for Vickers – later part of Vickers-Armstrongs and then part of the British Aircraft Corporation – until his retirement in 1971.

In April 1922, Wallis met his cousin-in-law, Molly Bloxam, at a family tea party. She was 17 and he was 34, and her father forbade them from courting. However, he allowed Wallis to assist Molly with her mathematics courses by correspondence, and they wrote some 250 letters, enlivening them with fictional characters such as "Duke Delta X". The letters gradually became personal, and Wallis proposed marriage on her 20th birthday. They were married on 23 April 1925, and remained so for 54 years until his death in 1979.

For 49 years, from 1930 until his death, Wallis lived with his family in Effingham, Surrey, and he is now buried at the local St. Lawrence Church together with his wife. His epitaph in Latin reads "Spernit Humum Fugiente Penna" (Severed from the earth with fleeting wing).

After the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe in 1939, Wallis saw a need for strategic bombing to destroy the enemy's ability to wage war and he wrote a paper entitled "A Note on a Method of Attacking the Axis Powers". Referring to the enemy's power supplies, he wrote (as Axiom 3): "If their destruction or paralysis can be accomplished they offer a means of rendering the enemy utterly incapable of continuing to prosecute the war". As a means to do this, he proposed huge bombs that could concentrate their force and destroy targets which were otherwise unlikely to be affected. Wallis's first super-large bomb design came out at some ten tonnes, far more than any current bomber could carry. Rather than drop the idea, this led him to suggest a plane that could carry it – the "Victory Bomber".

Two boxes of records, containing copies of key aeronautical papers written between 1940 and 1958, are held at the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge.

Early in 1942, Wallis began experimenting with skipping marbles over water tanks in his garden, leading to his April 1942 paper "Spherical Bomb — Surface Torpedo". The idea was that a bomb could skip over the water surface, avoiding torpedo nets, and sink directly next to a battleship or dam wall as a depth charge, with the surrounding water concentrating the force of the explosion on the target. A crucial innovation was the addition of backspin, which caused the bomb to trail behind the dropping aircraft (decreasing the chance of that aircraft being damaged by the force of the explosion below), increased the range of the bomb, and also prevented it from moving away from the target wall as it sank. After some initial scepticism, the Air Force accepted Wallis's bouncing bomb (codenamed Upkeep) for attacks on the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams in the Ruhr area. The raid on these dams in May 1943 (Operation Chastise) was immortalised in Paul Brickhill's 1951 book The Dam Busters and the 1955 film of the same name. The Möhne and Eder dams were successfully breached, causing damage to German factories and disrupting hydro-electric power.

Wallis became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1945 and was knighted in 1968. Wallis also received an Honorary Doctorate from Heriot-Watt University in 1969.

In the late 1950s, Wallis gave a lecture entitled "The strength of England" at Eton College, and continued to deliver versions of the talk into the early 1970s, presenting Technology and automation as a way to restore Britain's dominance. He advocated nuclear-powered cargo submarines as a means of making Britain immune to Future embargoes, and to make it a global trading power. He complained of the loss of aircraft design to the US, and suggested that Britain could dominate air travel by developing a small supersonic airliner capable of short take-off and landing.

He was awarded the sum of £10,000 for his war work from the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors. His grief at the loss of so many airmen in the dams raid was such that Wallis donated the entire sum to Christ's Hospital School in 1951 to allow them to set up the RAF Foundationers' Trust, allowing the children of RAF personnel killed or injured in action to attend the school.

In 1955 Wallis agreed to act as a consultant to the project to build the Parkes Radio Telescope in Australia. Some of the ideas he suggested are the same as or closely related to the final design, including the idea of supporting the dish at its centre, the geodetic structure of the dish and the master equatorial control system. Unhappy with the direction it had taken, Wallis left the project halfway into the design study and refused to accept his £1,000 consultant's fee.

"Swallow" was cancelled in the round of cuts following the Sandys Defence White Paper in 1957, and in an attempt to gain American funding to continue the work, details of the project were passed to the USA. No such funds were made available and Wallis's design ideas were passed over in the UK in favour of the BAC TSR-2 (on which one of Wallis's sons worked) and Concorde. Wallis was quite critical of both the TSR-2 and Concorde, stating that a swing-wing design would be more appropriate. In the mid-1960s, TSR-2 was ignominiously scrapped in favour of the American F-111 – which had swing wings based on Wallis's work which the Americans had received – although this order was also subsequently cancelled.

During the 1960s and into his retirement, he developed ideas for an "all-speed" aircraft, capable of efficient FLIGHT at all speed ranges from subsonic to hypersonic. In particular, his ideas and understanding of supersonic aerodynamics led to research that underwrote the design of the air intakes for Concorde's Olympus 593 engines. Using variable geometry air intakes, the Olympus engines were able to perform efficiently at all speeds from sub-sonic take-off and climb right through to supercruise at over Mach 2.

They had four children – Barnes (1926–2008), Mary (b. 1927), Elisabeth (b. 1933) and Christopher (1935–2006) – and also adopted Molly's sister's children when their parents were killed in an air raid.

Having been dispersed with the Design Office from Brooklands to the nearby Burhill Golf Club in Hersham, after the Vickers factory was badly bombed in September 1940, Wallis returned to Brooklands in November 1945 as Head of the Vickers-Armstrongs Research & Development Department and was based in the former motor circuit's 1907 Clubhouse. Here he and his staff worked on many Futuristic aerospace projects including supersonic FLIGHT and "swing-wing" Technology (later used in the Panavia Tornado and other aircraft types). A massive 19,533 square feet (1,814.7 m) Stratosphere Chamber (which was the world's largest facility of its type), was designed and built beside the Clubhouse by 1948 and became the focus for much R&D work under Wallis's direction in the 1950s and 1960s, including research into supersonic aerodynamics that contributed to the design of Concorde, before finally closing by 1980. This unique structure was restored at Brooklands Museum thanks to a grant from the AIM-Biffa Fund in 2013 and was officially reopened by Dr Mary Stopes-Roe (Barnes Wallis' daughter) on 13 March 2014.