| Who is it? | Nazi Party Ideologue, Author |

| Birth Day | January 12, 1893 |

| Birth Place | Tallinn, German |

| Age | 126 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 16 October 1946(1946-10-16) (aged 53)\nNuremberg, Germany |

| Birth Sign | Aquarius |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | None |

| President | Adolf Hitler (Führer) |

| Chancellor | Adolf Hitler (Führer) |

| Leader | Adolf Hitler |

| Cause of death | Hanging |

| Political party | National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) |

| Spouse(s) | Hilda Leesmann (m. 1915; div. 1923) Hedwig Kramer (m. 1925) |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | Riga Polytechnical Institute Moscow Highest Technical School |

| Profession | Architect, politician, writer |

| Cabinet | Hitler |

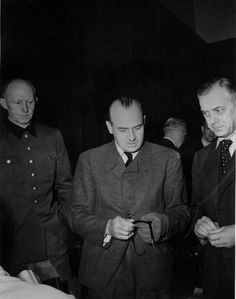

Alfred Rosenberg, a prominent figure in Nazi Germany, was a renowned Nazi Party ideologue and author in German. While his controversial ideologies continue to generate immense debate and condemnation, it is estimated that Alfred Rosenberg had accumulated a net worth of around $5 million by the year 2024. Despite his deeply divisive beliefs, Rosenberg's influence within the Nazi Party was undeniable, as he played a significant role in shaping their propaganda and ideological frameworks. However, it is crucial to distinguish net worth from the individual's actual merit or the ethical implications of their actions.

Some six million Jews still live in the East, and this question can only be solved by a biological extermination of the whole of Jewry in Europe. The Jewish Question will only be solved for Germany when the last Jew has left German territory, and for Europe when not a single Jew stands on the European continent as far as the Urals... And to this end it is necessary to force them beyond the Urals or otherwise bring about their eradication.

Rosenberg was married twice: to Hilda Leesmann (1891-1928), an ethnic Estonian, in 1915 (divorced in 1923), and to Hedwig Kramer in 1925, with whom he was married until his execution. He and Kramer had two children: a son who died in infancy and a daughter, Irene, who was born in 1930.

Rosenberg was born on 12 January 1893 in Tallinn in the Russian Empire, the capital of modern Estonia, to a family of Baltic Germans. His father, Waldemar Wilhelm Rosenberg, was a wealthy merchant from Latvia, and his mother, Elfriede (née Siré), was a Teacher of French language in Tallinn. The Hungarian-Jewish Journalist Franz Szell, who was apparently residing in Tilsit, Lithuania, spent a year researching in Latvian and Estonian archives before publishing in 1936 an open letter, with copies to Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels, German foreign minister Konstantin von Neurath, and others, accusing Rosenberg of having "no drop of German blood" flowing in his veins. Szell wrote that among Rosenberg's ancestors were only "Latvians, Jews, Mongols, and French." As a result of his open letter, Szell was deported by Lithuanian authorities on September 15, 1936. His claims were repeated in the 15 September 1937 issue of the Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano.

Lieutenant Colonel william Harold Dunn (1898–1955) wrote a medical and psychiatric report on him in prison to evaluate him as a suicide risk:

The young Rosenberg graduated from the Petri-Realschule (currently Tallinna Reaalkool) and went on to study architecture at the Riga Polytechnical Institute and engineering at Moscow's Highest Technical School completing his PhD studies in 1917. During his stays at home in Tallinn, he attended the art studio of the famed Painter Ants Laikmaa, but even though he showed promise, there are no records that he ever exhibited. During the German occupation in 1918, Rosenberg served as a Teacher at the Gustav Adolf Gymnasium. Rosenberg held his first speech on Jewish Marxism at the House of the Blackheads on 30 November after the outbreak of the Estonian War of Independence. He emigrated to Germany with the retreating imperial army, along with Max Scheubner-Richter, who served as something of a mentor to Rosenberg and to his ideology. Arriving in Munich, he contributed to Dietrich Eckart's publication, the Völkischer Beobachter (Ethnic/Nationalist Observer). By this time, he was both an antisemite – influenced by Houston Stewart Chamberlain's book The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, one of the key proto-Nazi books of racial theory – and an anti-bolshevik. Rosenberg became one of the earliest members of the German Workers' Party – later renamed the National Socialist German Workers' Party, better known as the Nazi Party – joining in January 1919, eight months before Adolf Hitler joined in September. According to some historians, Rosenberg had also been a member of the Thule Society, along with Eckart, although Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke contends that they were only guests. After the Völkischer Beobachter became the Nazi party newspaper in December 1920, Rosenberg became its Editor, in 1923. Rosenberg was a leading member of Aufbau Vereinigung, Reconstruction Organisation, a conspiratorial organisation of White Russian émigrés which had a critical influence on early Nazi policy.

Rosenberg convinced Hitler that communism was an international threat due to the fragility of the Soviet Union's internal political structure. "Jewish-Bolshevism" was accepted as a target for Nazism during the early 1920s.

Rosenberg got the racial term Untermensch from the title of Stoddard's 1922 book The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under-man, which had been adopted by the Nazis from that book's German version Der Kulturumsturz: Die Drohung des Untermenschen (1925).

In 1923, after the failed Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler, who had been imprisoned for treason, appointed Rosenberg as the leader of the National Socialist movement, a position he held until Hitler's release. Hitler remarked privately in later years that his choice of Rosenberg, whom he regarded as weak and lazy, was strategic; Hitler did not want the temporary leader of the Nazis to become too popular or hungry for power, because a person with either of those two qualities might not want to cede the party leadership after Hitler's release. However, at the time of the appointment Hitler had no reason to believe that he would soon be released, and Rosenberg had not appeared weak, so this may have been Hitler reading back into history his dissatisfaction with Rosenberg for the job he did.

In 1929 Rosenberg founded the Militant League for German Culture. He later formed the "Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question," dedicated to identifying and attacking Jewish influence in German culture and to recording the history of Judaism from a radical nationalist perspective. He became a Reichstag Deputy in 1930 and published his book on racial theory The Myth of the Twentieth Century (Der Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts) which deals with key issues in the National Socialist ideology, such as the "Jewish question." Rosenberg intended his book as a sequel to Houston Stewart Chamberlain's above-cited book. Despite selling more than a million copies by 1945, its influence within Nazism remains doubtful. It is often said to have been a book that was officially venerated within Nazism, but one that few had actually read beyond the first chapter or even found comprehensible. Hitler called it "stuff nobody can understand" and disapproved of its pseudo-religious tone.

Throughout the trial, it was agreed that Rosenberg had a decisive role in shaping Nazi philosophy and ideology. Examples include: his book, Myth of the Twentieth Century, which was published in 1930, where he incited hatred against "Liberal Imperialism" and "Bolshevik Marxism"; furthering the influence of the "Lebensraum" idea in Germany during the war; facilitating the persecution of Christian churches and the Jews in particular; and opposition to the Versailles Treaty.

After Hitler's assumption of power he moved to reassure the Protestant and Catholic churches that the party was not intending to reinstitute Germanic paganism. He placed himself in the position of being the man to save Positive Christianity from utter destruction at the hands of the atheistic antitheist Communists of the Soviet Union. This was especially true immediately before and after the elections of 1932; Hitler wanted to appear non-threatening to major Christian faiths and consolidate his power. Furthermore, Hitler felt that Catholic-Protestant infighting had been a major factor in weakening the German state and allowing its dominance by foreign powers.

The following year, once Hitler had become Chancellor, Rosenberg was named leader of the Nazi Party's foreign political office, but he played little practical part in the role. Another event of 1933 was Rosenberg's visit to Britain, intended to give the impression that the Nazis would not be a threat and to encourage links between the new regime and the British Empire. It was a notable failure. When Rosenberg laid a wreath bearing a swastika at the Cenotaph, a Labour Party candidate slashed it and later threw it in the Thames and was fined 40 shillings for willful damage at Bow Street magistrate’s court. In January 1934 Hitler granted Rosenberg responsibility for the spiritual and philosophical education of the Party and all related organizations.

In January 1934 Hitler had appointed Rosenberg as the cultural and educational leader of the Reich. The Sanctum Officium in Rome recommended that Rosenberg's Myth of the Twentieth Century be put on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (list of books forbidden by the Catholic Church) for scorning and rejecting "all dogmas of the Catholic Church, indeed the very fundamentals of the Christian religion". During World War II Rosenberg outlined the Future envisioned by the Hitler government for religion in Germany, with a thirty-point program for the Future of the German churches. Among its articles:

In 1940 Rosenberg was made head of the Hohe Schule (literally "high school", but the German phrase refers to a college), the Centre of National Socialist Ideological and Educational Research, out of which the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg developed for the purpose of looting art and cultural goods. The ERR were especially active in Paris in looting art stolen from famous Jewish families such as the Rothschilds and that of Paul Rosenberg. Hermann Göring used the ERR to collect art for his own personal gratification. He created a "Special Task Force for Music" (Sonderstab Musik) to collect the best musical instruments and scores for use in a university to be built in Hitler's home town of Linz, Austria. The orders given to the Sonderstab Musik were to loot all forms of Jewish property in Germany and of those found in any country taken over by the German army, and any musical instruments or scores were to be immediately shipped to Berlin.

In an 18 November 1941 press conference speaking about the Jewish Question, he said:

Amongst other things, Rosenberg issued a series of posters announcing the end of the Soviet collective farms (kolkhoz). He also issued an Agrarian Law in February 1942, annulling all Soviet legislation on farming and restoring family farms for those willing to collaborate with the occupiers. But decollectivisation conflicted with the wider demands of wartime food production, and Hermann Göring demanded that the collective farms be retained, save for a change of name. Hitler himself denounced the redistribution of land as "stupid".

He was sentenced to death and executed with other condemned co-defendants at Nuremberg Prison on the morning of 16 October 1946. His body, like those of the other nine executed men and that of Hermann Göring, was cremated at Ostfriedhof (Munich) and the ashes were scattered in the river Isar.

Rosenberg's handwritten diary, which had been used in evidence during the Nuremberg trials, went missing after the war along with other material which had been given to the prosecutor Robert Kempner (1899–1993). It was recovered in Lewiston, N.Y., on 13 June 2013. Written on 425 loose-leaf pages, with entries dating from 1936 through 1944, it is now the property of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington. Henry Mayer, the museum's senior archivist, and the son of a Holocaust survivor, was able to access the material and while "not given enough time to read [the] diary entry from beginning to end," he "could see that Rosenberg focused on certain subjects, including brutality against Jews and other ethnic groups and forcing the civilian population of occupied Russia to serve Germany." Meyer also noted Rosenberg's "hostile comments about Nazi Leaders," which he described as "unvarnished." While some parts of the manuscript had been previously published, the majority had been lost for decades. Former Federal Bureau of Investigation agent Robert King Wittman, who helped track down the diary, said, "there is no place in the diary where we have Rosenberg or Hitler saying the Jews should be exterminated, all it said was 'move them out of Europe'". The New York Times said of the search for the missing manuscript that "the tangled journey of the diary could itself be the subject of a television mini-series." Since the end of 2013, the USHMM has shown the 425-page document (photos and transcripts) on its homepage.