| Who is it? | Queen of Great Britain (1901-1910) |

| Birth Day | December 01, 1844 |

| Birth Place | Yellow Mansion, Copenhagen, Denmark, British |

| Age | 175 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 20 November 1925(1925-11-20) (aged 80)\nSandringham House, Norfolk |

| Birth Sign | Capricorn |

| Tenure | 22 January 1901 – 6 May 1910 |

| Coronation | 9 August 1902 |

| Burial | 28 November 1925 St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle |

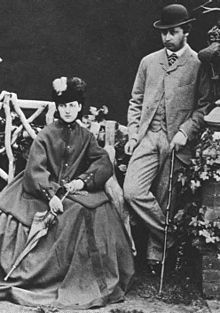

| Spouse | Edward VII (m. 1863; d. 1910) |

| Issue | Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence George V Louise, Princess Royal Princess Victoria Maud, Queen of Norway Prince Alexander John of Wales |

| Full name | Full name Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia |

| House | Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg |

| Father | Christian IX of Denmark |

| Mother | Louise of Hesse-Kassel |

Alexandra of Denmark, also renowned as the Queen of Great Britain from 1901 to 1910, is projected to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2025. She was not only a notable queen but also a symbol of elegance and grace during her reign. Her net worth is estimated based on various factors, including her royal inheritance, properties, investments, and other assets. Despite her passing over a century ago, Alexandra's legacy continues to hold value and fascination in British history.

Sea King's daughter from over the sea,

Alexandra!

Saxon and Norman and Dane are we,

But all of us Danes in our welcome of thee,

Alexandra!— A Welcome to Alexandra, Alfred, Lord Tennyson

In 1848, King Christian VIII of Denmark died and his only son, Frederick ascended the throne. Frederick was childless, had been through two unsuccessful marriages, and was assumed to be infertile. A succession crisis arose as Frederick ruled in both Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein, and the succession rules of each territory differed. In Holstein, the Salic law prevented inheritance through the female line, whereas no such restrictions applied in Denmark. Holstein, being predominantly German, proclaimed independence and called in the aid of Prussia. In 1852, the great powers called a conference in London to discuss the Danish succession. An uneasy peace was agreed, which included the provision that Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg would be Frederick's heir in all his dominions and the prior claims of others (who included Christian's own mother-in-law, brother-in-law and wife) were surrendered.

Her family had been relatively obscure until 1852, when her father, Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, was chosen with the consent of the great powers to succeed his distant cousin, Frederick VII, to the Danish throne. At the age of sixteen, she was chosen as the Future wife of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the heir apparent of Queen Victoria. They married eighteen months later in 1863, the same year her father became king of Denmark as Christian IX and her brother was appointed to the vacant Greek throne as George I. She was Princess of Wales from 1863 to 1901, the longest anyone has ever held that title, and became generally popular; her style of dress and bearing were copied by fashion-conscious women. Largely excluded from wielding any political power, she unsuccessfully attempted to sway the opinion of British ministers and her husband's family to favour Greek and Danish interests. Her public duties were restricted to uncontroversial involvement in charitable work.

On 24 September 1861, Crown Princess Victoria introduced her brother Albert Edward to Alexandra at Speyer. Almost a year later on 9 September 1862 (after his affair with Nellie Clifden and the death of his father) Albert Edward proposed to Alexandra at the Royal Castle of Laeken, the home of his great-uncle, King Leopold I of Belgium.

Alexandra was highly popular with the British public. After she married the Prince of Wales in 1863, a new park and "People's Palace", a public exhibition and arts centre under construction in north London, were renamed the Alexandra Palace and park to commemorate her. There are at least sixty-seven roads and streets in the Greater London area alone called Alexandra Road, Alexandra Avenue, Alexandra Gardens, Alexandra Close or Alexandra Street, all named after her. Unlike her husband and mother-in-law, she was not castigated by the press. Funds that she helped to collect were used to buy a river launch, called Alexandra, to ferry the wounded during the Sudan campaign, and to fit out a hospital ship, named The Princess of Wales, to bring back wounded from the Boer War. During the Boer War, Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service, later renamed Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps, was founded under Royal Warrant.

Alexandra's first child, Albert Victor, was born two months premature in early 1864. Alexandra showed devotion to her children: "She was in her glory when she could run up to the nursery, put on a flannel apron, wash the children herself and see them asleep in their little beds." Albert Edward and Alexandra had six children in total: Albert Victor, George, Louise, Victoria, Maud, and John. All of Alexandra's children were apparently born prematurely; biographer Richard Hough thought Alexandra deliberately misled Queen Victoria as to her probable delivery dates, as she did not want the queen to be present at their births. During the birth of her third child in 1867, the added complication of a bout of rheumatic fever threatened Alexandra's life, and left her with a permanent limp.

She hid a small scar on her neck, which was probably the result of a childhood operation, by wearing choker necklaces and high necklines, setting fashions which were adopted for fifty years. Alexandra's effect on fashion was so profound that society ladies even copied her limping gait, after her serious illness in 1867 left her with a stiff leg. This came to be known as the "Alexandra limp". She used predominantly the London fashion houses; her favourite was Redfern's, but she shopped occasionally at Doucet and Fromont of Paris.

Albert Edward and Alexandra visited Ireland in April 1868. After her illness the previous year, she had only just begun to walk again without the aid of two walking sticks, and was already pregnant with her fourth child. The royal couple undertook a six-month tour taking in Austria, Egypt and Greece over 1868 and 1869, which included visits to her brother King George I of Greece, to the Crimean battlefields and (for her only) to the harem of the Khedive Ismail. In Turkey she became the first woman to sit down to dinner with the Sultan (Abdülâziz).

The Waleses made Sandringham House their preferred residence, with Marlborough House their London base. Biographers agree that their marriage was in many ways a happy one; however, some have asserted that Albert Edward did not give his wife as much attention as she would have liked and that they gradually became estranged, until his attack of typhoid fever (the disease which was believed to have killed his father) in late 1871 brought about a reconciliation. This is disputed by others, who point out Alexandra's frequent pregnancies throughout this period and use family letters to deny the existence of any serious rift. Nevertheless, the Prince was severely criticised from many quarters of society for his apparent lack of interest in her very serious illness with rheumatic fever. Throughout their marriage Albert Edward continued to keep company with other women, including the Actress Lillie Langtry; Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick; humanitarian Agnes Keyser; and society matron Alice Keppel. Alexandra knew about most of these relationships, and later permitted Alice Keppel to visit the king as he lay dying. Alexandra herself remained faithful throughout her marriage.

For eight months over 1875–76, the Prince of Wales was absent from Britain on a tour of India, but to her dismay Alexandra was left behind. The Prince had planned an all-male group and intended to spend much of the time hunting and shooting. During the prince's tour, one of his friends who was travelling with him, Lord Aylesford, was told by his wife that she was going to leave him for another man: Lord Blandford, who was himself married. Aylesford was appalled and decided to seek a divorce. Meanwhile, Lord Blandford's brother, Lord Randolph Churchill, persuaded the lovers against an elopement. Now concerned by the threat of divorce, Lady Aylesford sought to dissuade her husband from proceeding but Lord Aylesford was Adam Ant and refused to reconsider. In an attempt to pressure Lord Aylesford to drop his divorce suit, Lady Aylesford and Lord Randolph Churchill called on Alexandra and told her that if the divorce was to proceed they would subpoena her husband as a witness and implicate him in the scandal. Distressed at their threats, and following the advice of Sir william Knollys and the Duchess of Teck, Alexandra informed the queen, who then wrote to the Prince of Wales. The Prince was incensed. Eventually, the Blandfords and the Aylesfords both separated privately. Although Lord Randolph Churchill later apologised, for years afterwards the Prince of Wales refused to speak to or see him.

Alexandra spent the spring of 1877 in Greece recuperating from a period of ill health and visiting her brother King George of Greece. During the Russo-Turkish War, Alexandra was clearly partial against Turkey and towards Russia, where her sister was married to the Tsarevitch, and she lobbied for a revision of the border between Greece and Turkey in favour of the Greeks. Alexandra and her two sons spent the next three years largely parted from each other's company as the boys were sent on a worldwide cruise as part of their naval and general education. The farewell was very tearful and, as shown by her regular letters, she missed them dreadfully. In 1881, Alexandra and Albert Edward travelled to Saint Petersburg after the assassination of Alexander II of Russia, both to represent Britain and so that Alexandra could provide comfort to her sister, who was now the Tsarina.

Alexandra undertook many public duties; in the words of Queen Victoria, "to spare me the strain and fatigue of functions. She opens bazaars, attends concerts, visits hospitals in my place ... she not only never complains, but endeavours to prove that she has enjoyed what to another would be a tiresome duty." She took a particular interest in the London Hospital, visiting it regularly. Joseph Merrick, the so-called "Elephant Man", was one of the patients whom she met. Crowds usually cheered Alexandra rapturously, but during a visit to Ireland in 1885, she suffered a rare moment of public hostility when visiting the City of Cork, a hotbed of Irish nationalism. She and her husband were booed by a crowd of two to three thousand people brandishing sticks and black flags. She smiled her way through the ordeal, which the British press still portrayed in a positive light, describing the crowds as "enthusiastic". As part of the same visit, she received a Doctorate in Music from Trinity College, Dublin.

Biographers have asserted that Alexandra was denied access to the king's briefing papers and excluded from some of his foreign tours to prevent her meddling in diplomatic matters. She was deeply distrustful of Germans, and invariably opposed anything that favoured German expansion or interests. For Example, in 1890 Alexandra wrote a memorandum, distributed to senior British ministers and military personnel, warning against the planned exchange of the British North Sea island of Heligoland for the German colony of Zanzibar, pointing out Heligoland's strategic significance and that it could be used either by Germany to launch an attack, or by Britain to contain German aggression. Despite this, the exchange went ahead anyway. The Germans fortified the island and, in the words of Robert Ensor and as Alexandra had predicted, it "became the keystone of Germany's maritime position for offence as well as for defence". The Frankfurter Zeitung was outspoken in its condemnation of Alexandra and her sister, the Dowager Empress of Russia, saying that the pair were "the centre of the international anti-German conspiracy". She despised and distrusted her nephew, German Emperor Wilhelm II, calling him in 1900 "inwardly our enemy".

The death of her eldest son, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, in 1892 was a serious blow to Alexandra. His room and possessions were kept exactly as he had left them, much as those of Prince Albert were left after his death in 1861. She said, "I have buried my angel and with him my happiness." Surviving letters between Alexandra and her children indicate that they were mutually devoted. In 1894, her brother-in-law Alexander III of Russia died and her nephew Nicholas II of Russia became Tsar. Alexandra's widowed sister, the Dowager Empress, leant heavily on her for support; Alexandra slept, prayed, and stayed beside her sister for the next two weeks until Alexander's burial.

Queen Alexandra's arms upon the ascension of her husband in 1901 were the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom impaled with the arms of her father, the King of Denmark. The shield is surmounted by the imperial crown, and supported by the crowned lion of England and a wild man or Savage from the Danish royal arms.

Among foreign honours received by Queen Alexandra was the Japanese Order of the Precious Crown, delivered to her on behalf of Emperor Meiji by Prince Komatsu Akihito when he visited the United Kingdom in June 1902 to attend the coronation. At the same time she also received the Order of Nishan-i-Sadakat from the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, despatched to London by a special messenger together with their coronation representatives.

Despite being queen, Alexandra's duties changed little, and she kept many of the same retainers. Alexandra's Woman of the Bedchamber, Charlotte Knollys, the daughter of Sir william Knollys, served Alexandra loyally for many years. On 10 December 1903, Knollys woke to find her bedroom full of smoke. She roused Alexandra and shepherded her to safety. In the words of Grand Duchess Augusta of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, "We must give credit to old Charlotte for really saving [Alexandra's] life."

Alexandra again looked after her grandchildren when George and Mary went on a second tour, this time to British India, over the winter of 1905–06. Her father, King Christian IX of Denmark, died that January. Eager to retain their family links, to each other and to Denmark, in 1907 Alexandra and her sister, the Dowager Empress of Russia, purchased a villa north of Copenhagen, Hvidøre, as a private getaway.

In 1910, Alexandra became the first queen consort to visit the British House of Commons during a debate. In a remarkable departure from precedent, for two hours she sat in the Ladies' Gallery overlooking the chamber while the Parliament Bill, a bill to remove the right of the House of Lords to veto legislation, was debated. Privately, Alexandra disagreed with the bill. Shortly afterward, she left to visit her brother, King George I of Greece, in Corfu. While there, she received news that King Edward was seriously ill. Alexandra returned at once and arrived just the day before her husband died. In his last hours, she personally administered oxygen from a gas cylinder to help him breathe. She told Frederick Ponsonby, "I feel as if I had been turned into stone, unable to cry, unable to grasp the meaning of it all." Later that year, she moved out of Buckingham Palace to Marlborough House, but she retained possession of Sandringham. The new king, Alexandra's son George, soon faced a decision over the Parliament Bill. Despite her personal views, Alexandra supported her son's reluctant agreement to Prime Minister H. H. Asquith's request to create sufficient Liberal peers after a general election if the Lords continued to block the legislation.

From Edward's death, Alexandra was queen mother, being a dowager queen and the mother of the reigning monarch. She did not attend her son's coronation in 1911 since it was not customary for a crowned queen to attend the coronation of another king or queen, but otherwise continued the public side of her life, devoting time to her charitable causes. One such cause included Alexandra Rose Day, where artificial roses made by people with disabilities were sold in aid of hospitals by women volunteers. During the First World War, the custom of hanging the banners of foreign princes invested with Britain's highest order of knighthood, the Order of the Garter, in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, came under criticism, as the German members of the Order were fighting against Britain. Alexandra joined calls to "have down those hateful German banners". Driven by public opinion, but against his own wishes, the king had the banners removed but to Alexandra's dismay he had down not only "those vile Prussian banners" but also those of her Hessian relations who were, in her opinion, "simply Soldiers or vassals under that brutal German Emperor's orders". On 17 September 1916, she was at Sandringham during a Zeppelin air raid, but far worse was to befall other members of her family. In Russia, her nephew Tsar Nicholas II was overthrown and he, his wife and children were killed by Revolutionaries. Her sister the Dowager Empress was rescued from Russia in 1919 by HMS Marlborough and brought to England, where she lived for some time with Alexandra.

In 1901, she became the first woman since 1488 to be made a Lady of the Garter. Other honours she held included Member First Class of the Royal Order of Victoria and Albert, Lady of the Imperial Order of the Crown of India, and Lady of Justice of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem. On 1 January 1918, she was appointed a Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire.

Alexandra retained a youthful appearance into her senior years, but during the war her age caught up with her. She took to wearing elaborate veils and heavy makeup, which was described by gossips as having her face "enamelled". She made no more trips abroad, and suffered increasing ill health. In 1920, a blood vessel in her eye burst, leaving her with temporary partial blindness. Towards the end of her life, her memory and speech became impaired. She died on 20 November 1925 at Sandringham after suffering a heart attack, and was buried in an elaborate tomb next to her husband in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.

The Queen Alexandra Memorial by Alfred Gilbert was unveiled on Alexandra Rose Day 8 June 1932 at Marlborough Gate, London. An ode in her memory, "So many true princesses who have gone", composed by the then Master of the King's Musick Sir Edward Elgar to words by the Poet Laureate John Masefield, was sung at the unveiling and conducted by the Composer.

Queen Alexandra has been portrayed on television by Deborah Grant and Helen Ryan in Edward the Seventh, Ann Firbank in Lillie, Maggie Smith in All the King's Men, and Bibi Andersson in The Lost Prince. She was portrayed in film by Helen Ryan again in the 1980 film The Elephant Man, Sara Stewart in the 1997 film Mrs Brown, and Julia Blake in the 1999 film Passion. In a 1980 stage play by Royce Ryton, Motherdear, she was portrayed by Margaret Lockwood in her last acting role.

Princess Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia, or "Alix", as her immediate family knew her, was born at the Yellow Palace, an 18th-century town house at 18 Amaliegade, right next to the Amalienborg Palace complex in Copenhagen. Her father was Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg and her mother was Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel. Although she was of royal blood, her family lived a comparatively normal life. They did not possess great wealth; her father's income from an army commission was about £800 per year and their house was a rent-free grace and favour property. Occasionally, Hans Christian Andersen was invited to call and tell the children stories before bedtime.