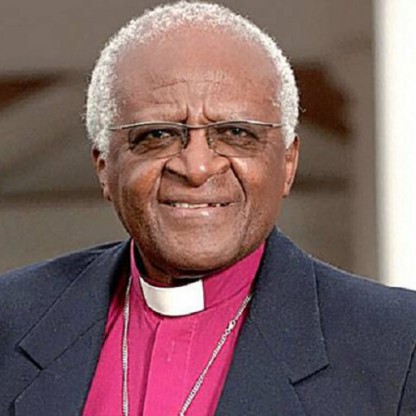

| Who is it? | Former Emperor of All Russia |

| Birth Day | March 10, 1845 |

| Birth Place | Saint Petersburg, Russian |

| Age | 174 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 1 November 1894(1894-11-01) (aged 49)\nMaley Palace, Livadia, Taurida Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| Reign | 13 March 1881 – 1 November 1894 |

| Coronation | 27 May 1883 |

| Predecessor | Alexander II |

| Successor | Nicholas II |

| Burial | 18 November 1894 Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Spouse | Dagmar of Denmark (m. 1866) |

| Issue Detail | Nicholas II of Russia Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich Grand Duke George Alexandrovich Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna |

| Full name | Full name Alexander Alexandrovich Romanov Alexander Alexandrovich Romanov |

| House | Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov |

| Father | Alexander II of Russia |

| Mother | Marie of Hesse |

| Religion | Russian Orthodox |

| Reference style | His Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

| Alternative style | Sir |

Alexander III of Russia, also known as the Former Emperor of All Russia in Russian, is believed to have a net worth ranging between $100,000 and $1 million in 2025. As one of the notable figures in Russian history, his wealth is attributed to various factors such as inheritances, royal possessions, and investments made by the Romanov dynasty. Despite facing financial challenges during his reign, Alexander III managed to leave a significant fortune behind. This estimate signifies his affluent status, recognizing his influence and role as a prominent ruler of the Russian Empire.

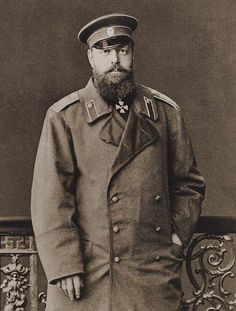

After a performance of the ballet Tsar Kandavl at the Mariinsky Theatre, I first caught sight of the Emperor. I was struck by the size of the man, and although cumbersome and heavy, he was still a mighty figure. There was indeed something of the muzhik [Russian peasant] about him. The look of his bright eyes made quite an impression on me. As he passed where I was standing, he raised his head for a second, and to this day I can remember what I felt as our eyes met. It was a look as cold as steel, in which there was something threatening, even frightening, and it struck me like a blow. The Tsar's gaze! The look of a man who stood above all others, but who carried a monstrous burden and who every minute had to fear for his life and the lives of those closest to him. In later years I came into contact with the Emperor on several occasions, and I felt not the slightest bit timid. In more ordinary cases Tsar Alexander III could be at once kind, simple, and even almost homely.

Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich was born on 10 March 1845 at the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, the second son and third child of Emperor Alexander II and his first wife Marie of Hesse.

Alexander became Tsesarevich upon Nicholas's sudden death in 1865; it was then that he began to study the principles of law and administration under Konstantin Pobedonostsev, then a professor of civil law at Moscow State University and later (from 1880) chief procurator of the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church in Russia. Pobedonostsev instilled into the young man's mind the belief that zeal for Russian Orthodox thought was an essential factor of Russian patriotism to be cultivated by every right-minded Emperor. While he was heir apparent from 1865 to 1881 Alexander did not play a prominent part in public affairs, but allowed it to become known that he had ideas which did not coincide with the principles of the existing government.

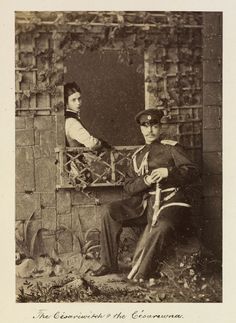

In the 1860s Alexander fell madly in love with his mother's lady-in-waiting, Princess Maria Elimovna Meshcherskaya. Dismayed to learn that Prince Wittgenstein had proposed to her in early 1866, he told his parents that he was prepared to give up his rights of succession in order to marry his beloved "Dusenka". On 19 May 1866, Alexander II informed his son that Russia had come to an agreement with the parents of Princess Dagmar of Denmark, his fourth cousin. Before then, she had been the fiancée of his late elder brother Nicholas. At first Alexander refused to travel to Copenhagen, declaring that he did not love Dagmar and his Desire to marry Maria. In response the enraged Emperor ordered Alexander to go straight to Denmark and propose to Princess Dagmar. The Tsesarevich then realised that he was not a free man and that duty had to come first and foremost; the only thing left to do was to write in his diary "Farewell, dear Dusenka." Maria was forced to leave Russia, accompanied by her aunt, Princess Chernyshova. Almost a year after her first appearance in Paris, Pavel Pavlovich Demidov, 2nd Prince di San Donato, fell in love with her and the couple married in 1867. Maria would die giving birth to her son Elim Pavlovich Demidov, 3rd Prince di San Donato. Alexander's reaction to the news of her death and the birth of her child is unknown.

Alexander soon grew fond of Dagmar and had six children by her, five of whom survived into adulthood: Nicholas (b. 1868), George (b. 1871), Xenia (b. 1875), Michael (b. 1878) and Olga (b. 1882). Of his five surviving children, he was closest to his youngest two. In 1885 it was Alexander who commissioned Peter Carl Fabergé to produce the first of what were to become a series of jeweled Easter eggs (now called "Fabergé eggs") for her as an Easter gift, the First Hen egg, which delighted her immensely and became an annual Easter tradition for Alexander and, upon his succession, for his son Nicholas as well.

Some differences had first appeared during the Franco-Prussian War, when Alexander II supported the cabinet of Berlin while the Tsesarevich made no effort to conceal his sympathies for the French. These sentiments would resurface during 1875-1879, when the Eastern Question excited Russian society. At first the Tsesarevich was more Slavophile than the government, but his phlegmatic nature restrained him from many exaggerations, and any popular illusions he may have imbibed were dispelled by personal observation in Bulgaria, where he commanded the left wing of the invading army. Never consulted on political questions, Alexander confined himself to military duties and fulfilled them in a conscientious and unobtrusive manner. After many mistakes and disappointments, the army reached Constantinople and the Treaty of San Stefano was signed, but much that had been obtained by that important document had to be sacrificed at the Congress of Berlin.

In such policies Alexander III had the encouragement of Konstantin Pobedonostsev, who retained control of the Church in Russia through his long tenure as Procurator of the Holy Synod (from 1880 to 1905) and who became tutor to Alexander's son and heir, Nicholas. (Pobedonostsev appears as "Toporov" in Tolstoy's novel Resurrection.) Other conservative advisors included Count D. A. Tolstoy (minister of education, and later of internal affairs) and I. N. Durnovo (D. A. Tolstoy's successor in the latter post). Mikhail Katkov and other journalists supported the Emperor in his autocracy.

On 1 March 1881 (O.S.) Alexander's father, Alexander II, was assassinated by members of the terrorist organization Narodnaya Volya. As a result, he ascended to the Russian imperial throne in Nennal on 13 March 1881. He and Maria Feodorovna were officially crowned and anointed at the Assumption Cathedral in Moscow on 27 May 1883. Alexander's ascent to the throne was followed by an outbreak of anti-Jewish riots.

All of Alexander III's internal reforms aimed to reverse the liberalization that had occurred in his father's reign. The new Emperor believed that remaining true to Russian Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality (the ideology introduced by his grandfather, Emperor Nicholas I) would save Russia from revolutionary agitation. Alexander's political ideal was a nation composed of a single nationality, language, and religion, as well as one form of administration. He attempted to realize this by the institution of mandatory teaching of the Russian language throughout the empire, including to his German, Polish, and other non-Russian subjects (with the exception of the Finns), by the patronization of Eastern Orthodoxy, by the destruction of the remnants of German, Polish, and Swedish institutions in the respective provinces, and by the weakening of Judaism through persecution of the Jews. The latter policy was implemented in the "May Laws" of 1882, which banned Jews from inhabiting rural areas and shtetls (even within the Pale of Settlement) and restricted the occupations in which they could engage.

Encouraged by its successful assassination of Alexander II, the Narodnaya Volya movement began planning the murder of Alexander III. The Okhrana uncovered the plot and five of the conspirators, including Alexander Ulyanov, the older brother of Vladimir Lenin, were captured and hanged on 20 May [O.S. 8 May] 1887.

On 29 October [O.S. 17 October] 1888 the Imperial train derailed in an accident at Borki. At the moment of the crash, the imperial family was in the dining car. Its roof collapsed, and Alexander supposedly held its remains on his shoulders as the children fled outdoors. The onset of Alexander’s kidney failure was later attributed to the blunt trauma suffered in this incident.

The famine of 1891–1892 and the ensuing cholera epidemic permitted some liberal activity, as the Russian government could not cope with the crisis and had to allow zemstvos to help with relief (among others, Tolstoy helped organize soup-kitchens, and Chekhov directed anti-cholera precautions in several villages).

In 1894, Alexander III became ill with terminal kidney disease (nephritis). Maria Fyodorovna's sister-in-law, Queen Olga of Greece, offered her villa of Mon Repos, on the island of Corfu, in the hope that it might improve the Tsar's condition. By the time that they reached Crimea, they stayed at the Maly Palace in Livadia, as Alexander was too weak to travel any further. Recognizing that the Tsar's days were numbered, various imperial relatives began to descend on Livadia. Even the famed clergyman John of Kronstadt paid a visit and administered Communion to the Tsar. On 21 October, Alexander received Nicholas's fiancée, Princess Alix, who had come from her native Darmstadt to receive the Tsar's blessing. Despite being exceedingly weak, Alexander insisted on receiving Alix in full dress uniform, an event that left him exhausted. Soon after, his health began to deteriorate more rapidly. He died in the arms of his wife, and in the presence of his physician, Ernst Viktor von Leyden, at Maly Palace in Livadia on the afternoon of 1 November [O.S. 20 October] 1894 at the age of forty-nine, and was succeeded by his eldest son Tsesarevich Nicholas, who took the throne as Nicholas II. After leaving Livadia on 6 November and traveling to St. Petersburg by way of Moscow, his remains were interred on 18 November at the Peter and Paul Fortress.

In 1909, a bronze Equestrian statue of Alexander III sculpted by Paolo Troubetzkoy was placed in Znamenskaya Square in front of the Moscow Rail Terminal in St. Petersburg. Both the horse and rider were sculpted in massive form, leading to the nickname of "hippopotamus". Troubetzkoy envisioned the statue as a caricature, jesting that he wished "to portray an animal atop another animal", and it was quite controversial at the time, with many, including the members of the Imperial Family, opposed to the design, but it was approved because of the Empress Dowager unexpectedly liking the monument. Following the Revolution of 1917 the statue remained in place as a symbol of tsarist autocracy until 1937 when it was placed in storage. In 1994 it was again put on public display, in front of the Marble Palace. Another memorial is located in the city of Irkutsk at the Angara embankment.

(Note: all dates prior to 1918 are in the Old Style Calendar)

As Tsesarevich—and then as Tsar—Alexander had an extremely poor relationship with his brother Grand Duke Vladimir. This tension was reflected in the rivalry between Maria Feodorovna and Vladimir's wife, Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna. Alexander had better relationships with his other brothers: Alexei (whom he made rear admiral and then a grand admiral of the Russian Navy), Sergei (whom he made governor of Moscow) and Paul.

On 18 November 2017, Vladimir Putin unveiled a bronze monument to Alexander III on the site of the former Maly Livadia Palace in Crimea. The four-meter monument by Russian Sculptor Andrey Kovalchuk depicts Alexander III sitting on a stump, his stretched arms resting on a sabre. An inscription repeats his alleged saying “Russia has only two allies: the Army and the Navy.”